Oregon has long, ugly ties to our country’s history of racism and discrimination.

In fact, when Oregon was granted statehood in 1859, our state constitution was the only one in the country that explicitly prohibited people of color from living, working, or owning property here. Immigrants were also looked down upon and frequently targeted by the federal government, which routinely used local and state resources to target immigrants.

Thankfully, progress has been made in the 100+ years since to eradicate our state’s discriminatory practices. Among the most important of these developments was passing a 1987 law that prevented local police and sheriff’s deputies from using local resources to enforce federal immigration law, effectively establishing Oregon as a “sanctuary state.” While there were many people involved in the effort to pass that bill, few deserve as much credit as Legislator Rocky Barilla.

Before the Bill, There Was Barilla

In 1975, Rocky Barilla was a young kid fresh out of law school who decided to move north from his home state of California to Salem, Oregon, settling for three years as an attorney at Marion-Polk Legal Aid Services of Oregon. At the time, Barilla–who is Latino–felt isolated.

“When I came up to Oregon, there were less than 20 attorneys in the State Bar who were people of color,” he recalls. “I couldn’t believe the blatant racism I experienced. When I was in Portland one day, people called out ‘Go home!’ It was awful.”

As the only person of color in his office, Barilla found himself immediately assigned to an immigration case. While this didn’t sit quite right, he had been taken aback by his recent encounters with racist Oregonians and accepted the case.

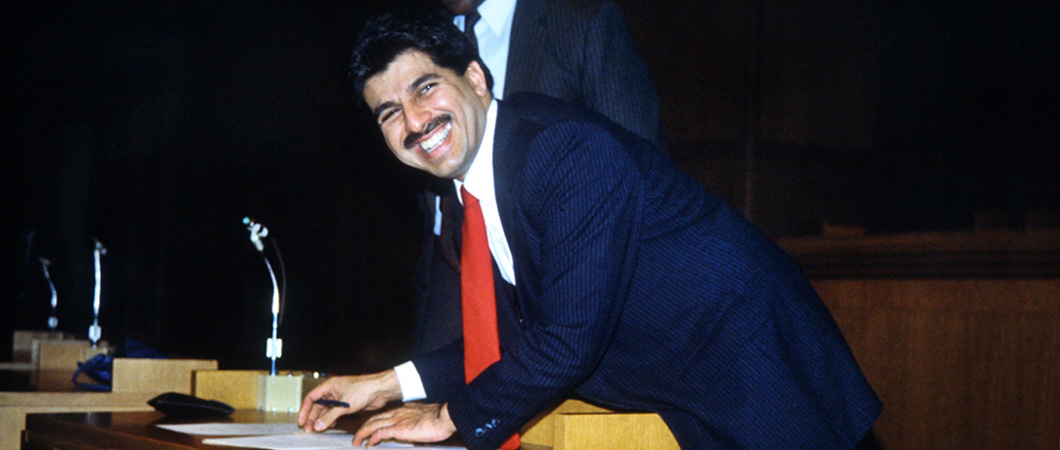

Rocky Barilla

“Pretty soon I found myself representing people from all over the world,” said Barilla. “Through time and exposure, I got pretty good at figuring out immigration law. Then one day, this guy walks into my office and says, ‘Hey, I’m a U.S. citizen, and I’ve been harassed by a local sheriff because I’m Chicano.”

That man was Delmiro Trevino, a U.S. citizen of Mexican descent who, unbeknownst to Barilla, would soon become the catalyst for much-needed reform in Oregon.

In the early morning hours of January 9, 1977, Trevino found himself with some friends at the Hi Ho Restaurant in Independence, Oregon. Soon, several police officers approached the men.

Without displaying a warrant or identification, Officer Janet Davidson and three Polk County sheriffs launched into an impromptu interrogation of the men regarding their immigration status.

One officer grabbed Trevino by the arm and forced him to stand in the middle of the restaurant in front of other customers. He was only released after Davidson identified him as a long-time resident of Independence.

Enraged, Trevino walked over to Barilla’s office and told him what he had just experienced. Barilla discovered that the Polk County had a de facto policy to drive around Latino neighborhoods and round up people they thought were undocumented immigrants. The sheriff’s office, at the behest of Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) would detain people of color, until INS could pick them up for deportation.

Trevino and Barilla filed a lawsuit accusing the officers of acting under the authorization of the INS. It was a success, even though the case was dismissed – Barilla managed to broker a deal with the U.S. Attorney’s Office saying INS would no longer encourage local law enforcement over the phone to enforce federal immigration law in Oregon. If they wanted to do so, INS agents would have to be physically present. While it wasn’t a flat-out ban on enforcement, it was an encouraging start.

A Law Years in the Making

By 1986, Barilla had made some big moves, becoming the first Latino elected to the Oregon Legislature. He was also involved with the local ACLU chapter, which was sponsoring a project called the Willamette Valley Immigration Project (WVIP), headed by Barilla’s good friend, Larry Kleinman. Kleinman was also one of the founders of PCUN, the largest farmworker union in the state of Oregon.

Kleinman was offered a grant from the ACLU to work on immigration rights and asked Barilla to help him out. Barilla agreed and provided Kleinman with legal support. After noticing his work, the ACLU, PCUN and several other groups eventually asked Barilla to sponsor a piece of legislation aimed at formally separating local law enforcement from federal immigration enforcement.

When he first approached police and members of both political parties to brief them on the law, Barilla made a surprising discovery.

“There was bipartisan support,” Barilla recalls. “Everybody saw the benefits of not using local resources to enforce federal law. The only concern of law enforcement was whether or not they could still enforce criminal behavior. If somebody commits a crime, they could continue to work together. But being in the country without documentation is not a crime.”

The lack of opposition to the law was refreshing. Local police officers no longer would be pressured to enforce immigration policies.

“There was no opposition to the bill at the time,” said Barilla. “Local law enforcement was excited to define and set their own priorities for law enforcement, to help defend against crimes against people and property.”

The bill passed the Oregon Senate and House easily: 29 to 1 and 58 to 1, respectively. It was signed into law on July 7, 1987.

Oregon’s Sanctuary Status Comes Under Attack

Now, efforts are underway across the country to repeal laws like Barilla’s that created protection for immigrants and people of color. Currently, Oregonians for Immigration Reform, which has strong ties to white supremacist networks, is collecting signatures to place a measure–Initiative Petition 22 (IP 22)–on the 2018 ballot, aimed at repealing the 1987 sanctuary law that has protected countless Oregonians from racial profiling for decades.

Community leaders are deeply concerned that if IP 22 passes, racial profiling will be much worse than it currently is, and could even create a return to the level of discrimination Barilla and other people of color experienced prior to the 1987 passing of his bill.

“We’ve seen a rise in white supremacy during the last decade with those seeking a return to the rampant discrimination and harassment of undocumented immigrants and communities of color,” says Barilla. “If Oregonians repeal our sanctuary law, we will see a dramatic increase in racial profiling and an erosion of community trust. I am hopeful Oregonians will stand up for immigrant communities.”

Take action, and reject racism and fear. Join One Oregon here.

We support immigrant protection

My grandfather (H. L. Moreno) and grandmother had to leave Southern Oregon in the late 1920s after it became too dangerous for them. Moved to California for 20 years and then came back and settled in Roseburg.

These efforts to make it possible for equal opportunities and peace are not taken for granted.

We appreciate all that has been done for people of color in our state.

Great articule.

Clatsop County ,Astoria Oregon should of abided by this in 2000 or 2001 when my friend go deported. Coruption.